It's always as easy as useless to predict the past |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

© Christian Müller 2021 |

||||

| «home | Prologue | |||

| On 8 May a LinkdIn post praising a new paper on the effects of a 2005 labour market reform in Germany strayed into my timeline (Hartz IV and the decline of German unemployment: A macroeconomic evaluation, Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control, vol. 127, 2021). In their paper Brigitte Hochmuth of University Erlangen-Nürnberg and co-authors claim to have determined why and the extent to which unemployment declined because of the 2005 reform. | ||||

| Always curious when someone makes quantitative causal statements I had a look at the article and soon realised that despite a lot of ingenious math wizz, sadly, the authors fell into a rather typical, yet subtle hindsight trap (Müller, Köberl, 2021, p.4). | ||||

| Having realised that I added this comment to the post «Looks very impressive and addresses a really important question! However, I wonder how firms could possibly form expectations back in 2005 along the lines of a model that hit the market sixteen years later, in 2021 [ref (3.1) etc.]? We also do not discuss the size and role of shift dummies and all those coefficients that are estimated with information available only after the fact.» to which one of the authors replied «Even if you do not like modern macro modelling (with search frictions and forward-looking expectations), there is good news: Appendix C shows that two recent papers with completely different methodologies (causal microeconometric estimations & structural VAR) deliver similar quantitative results». | ||||

| Of course, I was puzzled by this strange shift of focus and thus wrote back «Modern macro has very many powerful tools requiring utmost care when applying them. Agreed, that's not easy and sometimes fails like just seen. It may also very well be that other analyses yield similar results but that cannot count as support for the former.», and decided to offer my comments to the journal. | ||||

| Accordingly, I wrote to some of the editors of the journal (James Bullard, Herbert Dawid, Xuezhong He, Thomas Lubik) briefly referring to the flaw and suggested to publish a comment. Unfortunately, the journal's policy is that they «don’t typically publish comments», I learned from one editor's answer. | ||||

| Nonetheless, the editor in question also expressed the journal's interest in the problematic issues and asked for details. The following explanations heed this request. | ||||

| Innovations | ||||

| In order to understand the internal contradiction and eventual logical gaps in the argument it is worthwhile summarising a few key features of the paper. | ||||

| First, the authors rightfully claim that they offer a rather long list of innovations. Among them are the following model features: «Our model combines three ingredients: First, workers and firms meet randomly. Meetings are driven by a Cobb-Douglas constant returns contact function (Mortensen and Pissarides, 1994). Second, upon meeting, only a certain fraction of contacts is hired. All meetings draw an idiosyncratic training cost shock from a stable density function (see Chugh and Merkl, 2016 or Sedlácek, 2014). Firms only select workers with an expected positive present value. Third, as Hartz IV was a reform of long-term unemployment benefits, we model a detailed deterministic unemployment structure.» (Hochmuth et al., 2021, p. 3). | ||||

| This combination is indeed rather unique and together with applying several other clever tricks and data certainly justifies their conclusion, namely that «This paper proposes a novel approach how to evaluate the reform of the German unemployment benefits system in 2005.» (Hochmuth et al., 2021, p. 21). | ||||

| In sum, there can be no doubt that the model presented by the authors is indeed new and certainly not older than three years when, according to the footnote at the top page, the paper was first presented at seminars. | ||||

| Some model features | ||||

| The model whose simulations lead the authors to find that the labour market reforms have reduced «steady state unemployment» by 2.1 percentage points emulates the position of firms and workers prior to the reform by letting firms form expectations about profits (eq. 3.1) and workers maximising the sum of income from labour and unemployment benefits (section 3.2., 3.3) subject to several restrictions. | ||||

| The list of restrictions, the previously mentioned job search, matching and hiring mechanism, the institutional setting etc. complete the model. | ||||

| The model is eventually solved «for the transition to the post-reform steady state under perfect foresight» (p. 15). | ||||

| Lapse #1 | ||||

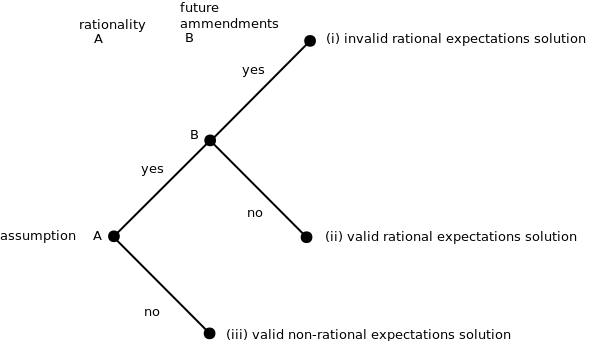

| From the above it should already be obvious that there is no chance that any firm or worker could have based its 2004/2005 pre-transition decisions on a model which is a 2021 (earliest 2018) innovation. Therefore, whatever shock struck or whatever reform was introduced, workers' and firms' reactions could not evolve along the lines of this novel model. | ||||

| There is also no way of «curing» the lack of knowledge of the model by assuming perfect foresight for firms or workers (instead of only for the modellers) as that would violate the innovativeness claim discussed above. I.e. if it was true that firms and workers could also forecast the 2018/2021 model in 2005 already, the claim that the paper offers any new insight or model innovation would be misplaced and all credit should go to these workers and firms. | ||||

| In short, the model proposed by the authors yields zero insights into the effects of the 2005 labour market reform as it is totally uninformative about what people could possibly think or do back then. Therefore, the paper does not add anything to our understanding of what measure caused what effect in the context of the 2005 labour market reform. | ||||

| Lapse #2 | ||||

| To wrap things up, it should also be noted that much of the information that is exploited to solve the model was not available at the time it would have been needed by decision makers. For instance, the target used for calibration (the increase of the average selection rate) is estimated with the help of post-reform data and was, naturally, not available to decision makers prior to the reform. This too, shows that the approach of modelling key actors' decisions simply fails as the only fact that is known with certainty is, that firms and workers did not behave according to the model. | ||||

| In principle, it could of course be assumed that workers and firms perfectly predicted the realisations of the data used for estimation as well as the results owed to Klinger and Rothe (2012) which enter the model as parameters and so on. But if that should have been the case, the authors of Hartz IV and the decline of German unemployment: A macroeconomic evaluation should also be able to explain how they were able to do so in the first place. Not being able to so shows that the paper ultimately lacks the required rigor. | ||||

| Words of solace | ||||

| While there is nothing to learn from the paper about the past it may, for the same reasons, be helpful in the future. In a hypothetical situation similar to pre-2005 Germany with labour reform plans on the table and politicians guessing what the outcome might be, Hochmuth et al. (2021) may serve as a reference point. If so, we would immediately see that experts would argue about the model specification as well as about the correct choices of parameters and calibration benchmarks which are - against the authors' assumption - not perfectly forecastable in reality. Decisions would be made considering model as well as parameter ambiguities, and years after the fact, researchers would quite well understand what happened and how the outcome might have been improved had certain - as yet unknown - issues been paid more attention to. | ||||

| Conclusion | ||||

| The question posited by Brigitte Hochmuth and co-authors is very important because understanding the mechanism of labour market reforms potentially helps policy makers and stakeholders in general to devise better policies. A perfectly sensible way is to put oneself in the shoes of economic agents who are about to take dicisions and sort out the optimal behaviour depending on the best possible expectations. The authors chose differently. Instead of modelling the expectations of agents prior to the reform they took an ex-post perspective that is naturally totally uninformative about the actual events since it negates the key foundations of expectations-based economic modelling. | ||||

| Unfortunately, this uninformative modelling approach is much more popular than it should be. For example, forecasters pretty often also step into similar traps as explained in Müller and Köberl (2021). Consequently, the only sober way out of the logical flaws within the decision simulation modelling approach exemplified above would be to really confine oneself to the information truly available at decision time. Better still, a careful documentation of decision makers' position and considerations prior to the fact could be key for drawing valid conclusions ex-post. | ||||

| Hochmuth et al.'s paper may be part of an according documentation should a similar reform project be on the cards some time, somewhere in the future. | ||||

| References | ||||

| Hochmuth, Brigitte; Kohlbrecher, Britta; Merkl, Christian; Gartner, Hermann, Hartz IV and the decline of German unemployment: A macroeconomic evaluation, Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control, vol. 127, 2021. | ||||

| Köberl, Eva; Müller, Christian, Catching a floating treasure A genuine ex-ante forecasting experiment in real time, KOF Working Papers, 2012-01, https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-006959225. | ||||

| Rothe, T., Wälde, K., 2017. Where Did All the Unemployed Go? Non-standard Work in Germany after the Hartz Reforms. Discussion Paper. Gutenberg School of Management and Economics & Research Unit Interdisciplinary Public Policy. | ||||

| Further reading | ||||

| A BEHAVIORAL NEW KEYNESIAN MODELL | ||||

| Clearing Up the Fiscal Multiplier Morass: A comment | ||||

| Spooky neoclassics | ||||

| „Fukuyama models“ – a re-appraisal of the Lucas critique | ||||

| Uncertainty and Economics: A paradigmatic perspective, London and New York: Routledge | ||||

| «home | ||||

| © Christian Müller 2021 | ||||

| Jacobs University Bremen | ||||

| www.s-e-i.ch | ||||